Organised opposition to Communist influence in trade unions had already begun in the late 1930s. Sections of the Catholic Church, especially in Melbourne, used the wider organisation of Catholic Action to set up a specific body known as 'The Movement' to help contest union elections against Communists. This was led by a Melbourne activist, BA Santamaria, who had the full support of Archbishop Mannix. It was also supported by some parliamentary members of the ALP, especially in Victoria. By the end of the war it was clear that, although Communist influence in strategic unions was no longer expanding, Communist industrial militancy was intensifying. In that situation the NSW Branch, at its Annual Conference in 1945, decided to establish 'Industrial Groups' to promote Labor candidates in trade union elections.

Other States followed quickly, so that very soon the 'Groupers' became a force to be reckoned with not only in trade union elections but inside the Labor Party itself. A number of prominent supporters of the Industrial Groups, like Dr Lloyd Ross of the Australian Railways Union, had themselves previously been involved with the Communist Party. As the Groupers wrested control of key unions from Communists they found themselves enjoying access to the extra-parliamentary machinery of the ALP in ways that gave them added influence. By 1950 Groupers were dominant in the Victorian Branch and in a strong position in New South Wales.

The rise of the Groupers had some interesting parallels with the threat from Communists. Both could be portrayed, not necessarily accurately, as attempts by foreign based bodies (Moscow or the Vatican) to infiltrate and control the Labor Party. Both were committed to secrecy and to the use of anti-democratic tactics such as ballot rigging to achieve success. Neither was established specifically to control the Labor Party, but both at times found themselves in a position where it might become possible. Both, it needs to be acknowledged, were challenges that the ALP had to face and reduce.

At some stages of the party's history factions have been the source of new ideas and constructive compromises that any party with an appeal to the whole electorate must encourage. Certainly the Labor Party needs ideas from both the left and the right. By the 1950s a pattern of regular factional competition was apparent throughout the ALP, with control maintained by a well organised Right faction or by its mirror image on the Left. Thus, Federal Conference and the Federal Executive were also tightly factionalised. State machines in NSW and Queensland were controlled by the Right, with Grouper support; in Victoria a Grouper-dominated Right had replaced the traditional Left; in the other states the Left tended to be dominant. It is of the nature of factionalism that internal factions, or fractions, should compete for power. Within the Right there was competition, and some sharing of power, between the government support groups in Queensland and NSW, along with the AWU, and the newer Groupers. Within the Left there were various shades of industrial and political militancy, with regular accusations, even inside the party, that the more aggressive sections were at least sympathetic to Communists.

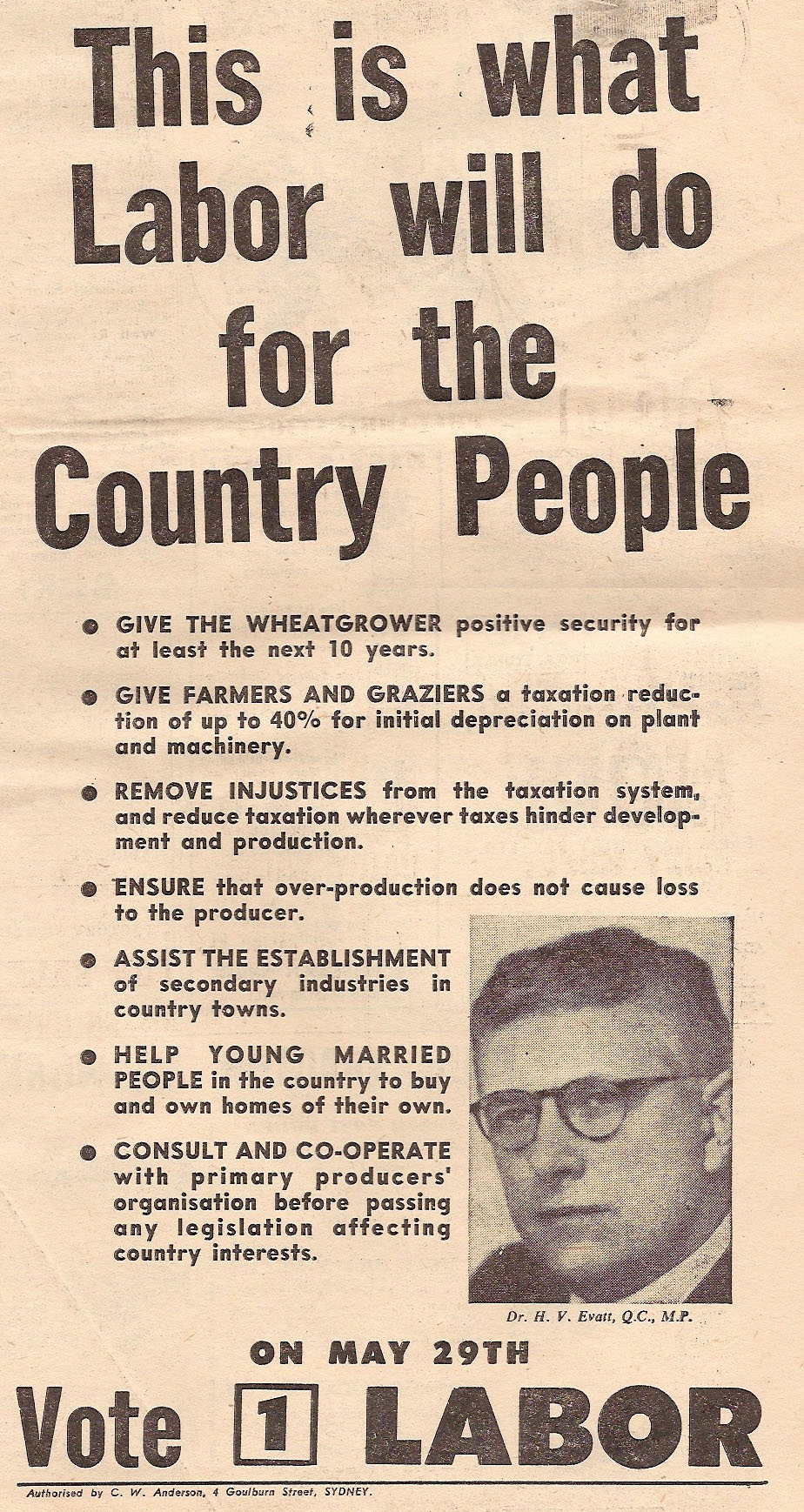

Prime Minister Menzies called an election for May 1954 that was dominated by the issue of Communism. Dr. Evatt, who had replaced Chifley in 1951 as leader of the party, was convinced that Labor would win the election because of the unpopularity of the Menzies government in the aftermath of the Korean War which had caused difficulties with inflation. Moreover, the result of that war had been a disappointment for anti-Communists in Australia. Evatt had already achieved a victory over Menzies by successfully pressing for a NO vote in the referendum on banning the Communist Party and was convinced that the issue would not damage Labor in the election. However the dramatic events of the defection of Soviet spy Vladimir Petrov and his wife in April 1954 became an embarrassment for Labor when Menzies appointed a Royal Commission on the affair that threatened to implicate Labor figures in Soviet espionage. Even despite this sensation the election was extremely close; Menzies was returned to office but lost five seats, while Labor won a majority of the primary votes but still lost the contest. After the election Evatt's political judgement abandoned him when he produced a letter in Parliament from Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov, denying any Soviet involvement in espionage in Australia.