In the Commonwealth Parliament the members of Caucus who remained in the Labor Party elected Frank Tudor as leader. Almost immediately he had to prepare for an election which was held in May 1917. Hughes won a landslide victory, leaving Labor with only 22 seats out of the 75 in the House of Representatives, and gaining control of the Senate. Similar situations prevailed in the States. While TJ Ryan remained Labor Premier in Queensland, elections in NSW (1917), Victoria (1917), Western Australia (1917), and South Australia (1918), saw Labor representation drastically reduced to levels comparable to that in the Commonwealth. Tasmania, with its Proportional Representation system of voting, left Labor in a minority, but within reach.

If the consequences of the split were disastrous in the parliamentary arena, that was only temporary, and within an election or two Labor was able to compete effectively. It even won the following election in NSW in 1920 an amazing regeneration considering the damage done. However, it was within the general party structures and culture that more permanent changes were evident. The most obvious damage was the loss of so many talented men, who were reviled now as 'rats'. Yet no party can suddenly lose people of the calibre of Hughes, Holman, Watson, McGowen, Griffith, Vaughan, Scaddan, and so many others without losing part of its soul. The more permanent changes were at lower levels of the party. Paradoxically, there were simultaneous tendencies both to radicalise the labour movement and to give it a more conservative base.

In the extra-parliamentary sections of the party the 'Industrialists' were now firmly in control and intent on leaning on their elected representatives to implement the full industrial and social program. Within that group there soon emerged a fierce rivalry between a moderate AWU and a group of more militant unions who took inspiration from the 1917 revolutions in Russia, and from the IWW, to demand more radical policies t. By the end of 1917 many of the more radical trade unionists and ideologues realised that they would have more freedom to present these ideas outside the party. Various socialist parties (and by 1920 the Communist Party) emerged on the left of the ALP. Many of these (Albert Willis and Jock Garden two of the most prominent) would return to the Labor Party within a few years, to promote a left agenda within the party and lead a recognisable left wing of the party.

The expulsion of the conscriptionists had an unforeseen consequence on the right of the party. Overwhelmingly the ones who had gone were Protestants, and a strong Protestant reform tradition that had driven the party from the beginning almost disappeared. Prominent members of the party seemed to number many more Irish (and Catholic) names than previously. It was not a Catholic takeover and the Labor Party continued its original tradition of regarding sectarian issues as electoral suicide. Nor were Catholics at this stage confined to the right of the party. Nevertheless, from this time dates the emergence of a recognisable extra-parliamentary right wing of the party whose members preferred pragmatic and socially conservative policies that could be presented as appealing to middle-of-the-road voters.

By 1918, once the conscription split had been consummated, most members of the Labor Party would have regarded the issue of conscription as having sorted out the major division in the party between the parliamentary and the extra-parliamentary party. Surely now the MPs would have learned the lesson that they were servants of the movement and the wider party. However, that book still had many more chapters to be written.

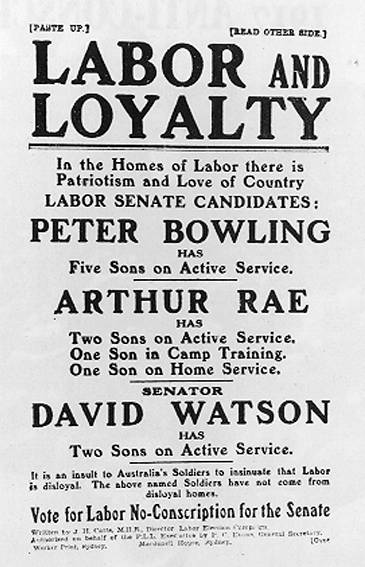

One reason that the conscription split was so bitter was that both sides were convinced that their stance was completely principled and moral. This was not just politics-as-usual, where people could oppose one another on individual issues then later meet as friends at the races or at the parliamentary bar. Opposition to conscription for overseas service was deeply entrenched in the culture of the Labor Party, based on values of fairness and justice. Most Labor Party members (judging from their contributions to State Conferences at the time) supported voluntary enlistment, and indeed a number of Labor MPs volunteered, served, and died in the war.

Labor policy was that conscription was available for defence of the homeland Australia but not to inflate the imperial ambitions of Britain. That point had been made time and again around the turn of the century about Australian participation in the Boer War and the Sudan War, and made forcefully by leaders like Hughes and Holman. Added to this basic principle was a more radical principle of fairness that if Australian governments were not willing to conscript capital to nationalise industries for the war effort then they should not be allowed to conscript labour. On the other side of the split leaders like Hughes and Holman, along with approximately half the population of Australia, considered that the Great War was a struggle for the survival of the British Empire, of which they were loyal subjects. It thus became a choice of loyalties; should one's first loyalty be to a political party or to one's King and country? Choices were made and former colleagues became enemies forever. In most Labor Party splits peace is made between former enemies after a short period of time. But not with the conscription split. The Labor Party remained resolute in refusing re-admission to any former member who had opposed it on conscription. For many years Billy Hughes regarded himself as a Labor Party member at heart, even if not welcome in the party. He was one of the founders of the party; his original principles and ideals still informed it.