Labor’s new term in office was overshadowed by a protracted economic slowdown and the culmination of the leadership struggle between the Prime Minister and Treasurer. While the Reserve Bank cut interest rates in April, August and November of 1990, this was too little and too late to reverse an inexorable slide in economic activity. GDP growth flatlined in the June quarter. When the data was released for the September quarter, showing sharply negative growth, Keating explained to a media conference that ‘this is a recession that Australia had to have.’ His words made it seem the government had uncaringly, even deliberately, engineered the circumstances that threw hundreds of thousands of Australians out of work and caused small business collapses throughout the land. The December quarter GDP returned to growth, but unemployment hit 8% and continued to rise.

The slowdown did not blunt the Labor government’s enthusiasm for further micro-economic reform. Attention turned to the need for competition in sectors dominated by the government’s own major enterprises – airlines, banking and telecommunications. Under the prevailing orthodoxy, economists argued government investment in such sectors was inefficient, relative to private operators, and diverted public resources away from more pressing purposes. Qantas and Australian Airlines were merged, and required to compete internationally with the other private domestic airline Ansett. The government-owned Commonwealth Bank was part-privatised to raise capital for the purchase (in reality, bail-out) of the troubled State Bank of Victoria.

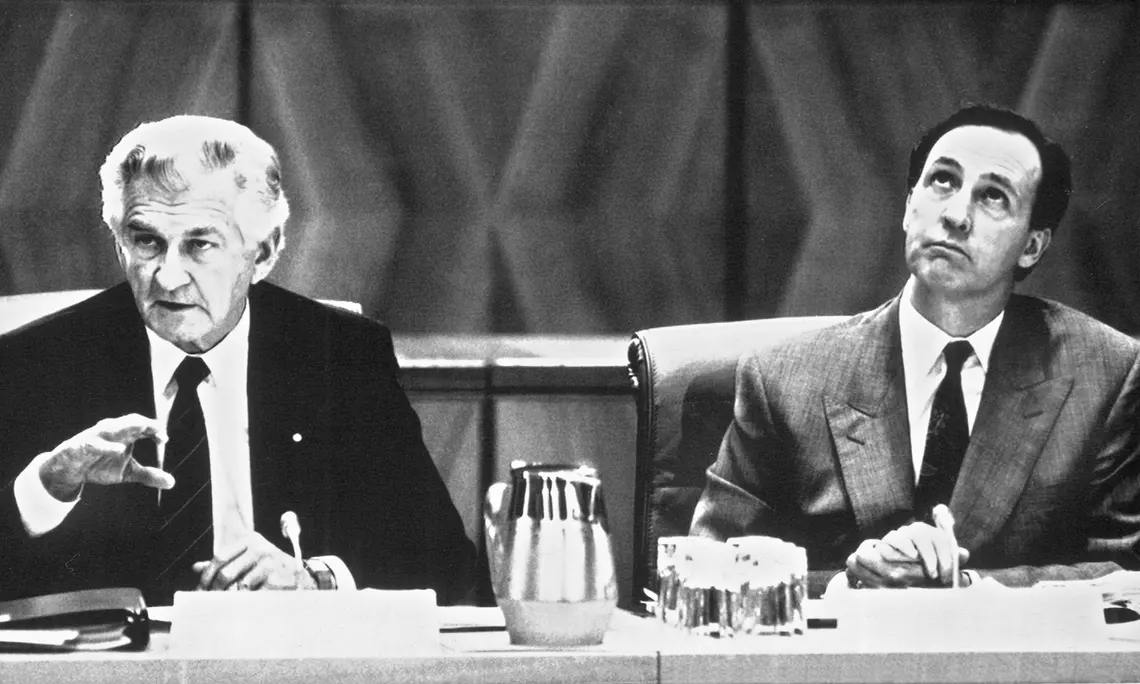

Even greater turbulence was generated - within the party, and within Cabinet – by the government’s plan to shake up the vast and lucrative telecommunications sector, dominated by the government monopoly Telecom. Hawke and Transport and Communications Minister Kim Beazley proposed to merge Telecom with the government-owned Overseas Telecommunications Corporation (OTC), and to create a competitor to this behemoth by selling off satellite operator AUSSAT to a new entrant in the private sector. Keating – now elevated to Deputy Prime Minister following the retirement of Lionel Bowen – strongly disagreed, but was defeated in a bruising and personal Cabinet debate. Beazley’s plan was then submitted to an ALP Special National Conference in September 1990, which approved the necessary changes to the party platform.

The ALP had long championed public ownership of key economic institutions. In 1911, under Fisher, it had established the Commonwealth Bank. In 1949, under Chifley, had campaigned to nationalise the entire banking system, these privatisations caused deep unease. Sections of Labor’s left-wing bitterly opposed them, and indeed regarded much of the Hawke Government’s economic program, in the words of one academic study, as a ‘Hawke-Keating Hijack’.

The Prime Minister and Treasurer themselves were, as ever, unapologetic. They never favoured ideological orthodoxy or party tradition over pragmatic, instrumental reforms to respond to the national economic challenge. They observed the spirit if not the strict letter of the party platform, and usually managed to drag the caucus, faction leaders and party conferences along with them. Thus, at the 1990 Special National Conference, Hawke reminded Labor of its ‘great unchangeable goal 'over nearly one hundred years of existence:

‘It is not a complex goal. You do not need to be versed in political science to understand what that fundamental goal, through all the vicissitudes of war, depression and internal upheaval, has been. It has simply been the goal of the improvement of the lives of ordinary Australians. That is what the party is all about. … What we are about here [at the conference] is adherence to the fundamental Labor goal of advancing the interests of ordinary Australians.’

In March 1991, Hawke’s ‘Building a Competitive Australia’ statement announced further tariff cuts – the general rate down from 15 and 10% to 5% by 1996, with further cuts in support for the car and textiles industries – along with reduced wholesale taxes for business and simpler depreciation. Retraining and apprenticeship initiatives, along with Cooperative Research Centres - new research vehicles combining university and industry researchers – would contribute to a vision of Australia as a ‘clever country’. Meanwhile, the sluggish economy slowed further, with negative growth in the March and June quarters of 1991: a full-blown recession. Unemployment topped 9% in March and continued to rise. Hawke echoed Treasury forecasts that the economy would return to growth in the second half of 1991.

The Iraq War and Leadership Tensions

The Hawke Government broke new ground in another field, committing Australian defence forces to combat for the first time since Vietnam. In August 1990 Iraqi forces under the leadership of Saddam Hussein invaded neighbouring Kuwait. The United Nations imposed sanctions against Iraq and, when these proved insufficiently persuasive, in November authorised member states to eject Iraqi forces from Kuwait using ‘all necessary means.’

Australia sent two RAN frigates and a supply ship to the Persian Gulf region to help enforce the sanctions. These vessels, along with a team of mine-clearance divers, joined the US-led multinational coalition that assembled to achieve the United Nations’ will.

In Parliament, Cabinet and the ALP Caucus, Hawke argued the strategy and rationale for war: it was essential in this new post-Cold War environment to uphold the international rule of law, not to reward aggression as had happened in the 1930s. While he coordinated Australia’s response closely with US President George H. W. Bush, the Gulf engagement was not an ANZUS alliance commitment. Instead it represented the culmination of Labor’s program of engaged multilateralism; the critical authorisation was provided by the UN Security Council. Aerial bombardment and land operations crushed the Iraqi armed forces in January and February 1991; Australian forces returned home without casualty.

Meanwhile, however, the Hawke-Keating rivalry entered a new downward spiral. In December 1990, shocked by the sudden death the previous day of Treasury Secretary Chris Higgins, and anxiously awaiting the leadership transition promised him at Kirribilli House, Keating took the opportunity of a supposedly ‘off-the-record’ speech to the annual Press Gallery dinner to ruminate on political leadership. Australia’s problem, he thought, was that it had never had a great leader in times of crisis – Curtin was only ‘a trier’, and Chifley ‘a plodder’. Keating described himself as ‘the Placido Domingo of Australian politics.’ Leadership, he declared, was about being ‘right and strong’, not about being popular: not – a dismissive flick at Hawke - about ‘tripping over television cables in shopping centres’.

The provocation was immediately reported in luxurious detail. Hawke summoned Keating, and in a protracted dialogue they tested their rival claims to Labor leadership in the 1990s by reference to their rival proxies from Labor’s past: Hawke, the champion of Western Australian wartime leader John Curtin, against Keating, who had learned his trade at the knees of Jack Lang, the ‘Big Fella’ from NSW and one of Curtin’s most destructive opponents. Keating insisted it was his time to lead: Hawke could step down with dignity once Saddam Hussein was gone. Hawke resisted, asserting only he could lead Labor to another victory in 1993. Hawke decided to repudiate the Kirribilli agreement and told Keating all bets were off.

On Thursday 30 May 1991, the Kirribilli agreement was leaked, generating shock waves in the media and community. Keating told Hawke he would challenge him for the leadership. Confident of his numbers, Hawke convened caucus for Friday morning; but he’d failed to anticipate Keating’s refusal to move for a spill. The meeting fizzed into anti-climax. In a surreal scene, the rivals then immediately teamed up to represent the Commonwealth at a meeting with the State Premiers. Caucus met again after the weekend, and Hawke won the ballot by 66 votes to 44. Keating retired to the backbench, telling journalists, ‘I had only one shot in my locker and I fired it.’

Keating was replaced as deputy PM by Brian Howe, and as Treasurer by John Kerin. With the Treasury urging no relaxation in fiscal discipline, Kerin’s August Federal Budget required new spending initiatives to be offset by savings elsewhere. A proposed Medicare co-payment – a flat fee for visits to a GP, intended as a brake on over-servicing - proved deeply unpopular. From the backbench, Keating used the uproar to agitate for more spending, lower interest rates, and abolition of the co-payment. He also deftly derailed Hawke’s New Federalism initiative, aimed at rebalancing Commonwealth-state financial arrangements; Keating labelled it a plan for state income taxes. Keating’s standing in the media, and more importantly in the ALP Federal Caucus, strengthened.

The leadership battle had delayed Cabinet consideration of whether to permit mining at Coronation Hill, a site within, but not part of, the Kakadu National Park. Business pressured the Hawke Government to approve the mine; Keating and, even in his absence, a majority of ministers agreed. But for the Jawoyn traditional owners, the site represented an important part of their Bula creation story. A Resource Assessment Commission inquiry found a properly managed mine could proceed without great risk to the environment of Kakadu – but confirmed that mining would be against the wishes of the Jawoyn. In June 1991, Hawke’s passionate defence of the Jawoyn belief system won the day in Cabinet – but his leadership authority was further weakened.