Immediately after the election, Hawke restructured the Commonwealth public service, amalgamating smaller ministries into ‘super’ departments covering larger portfolio areas. This yielded administrative efficiencies by reducing the total number of separate departments (from 27 to 16), while also satisfying the ambitions of backbenchers and factions with an increased number of ministers (from 27 to 30).

This was the first instalment of the sweeping micro-economic reforms that Hawke had promised in the election campaign and that were energetically pursued by the Labor Government throughout the third term. The reform agenda recognised that much of the regulatory structure, erected to protect Australian manufacturing from international competition in the decades following the Second World War, was no longer fit for purpose. Indeed, especially following the floating of the dollar and other financial sector reforms, it had become counter-productive: industry protection served now only to stifle innovation, increase retail prices, and hold back growth.

Backed by research by a reinvigorated Industry Commission, Labor set about dismantling sectoral industry protection and removing subsidies. General levels of tariffs were cut to 15%, falling to 10% in 1992. Quotas on motor vehicle imports were removed and tariffs reduced. Dairy and other agricultural subsidies were converted to tariffs and these too were phased down.

Likewise, Labor also introduced competition and improved efficiency in sectors distorted by regulation and other interventions. Labor abolished the two-airlines agreement, introduced user-pays pricing of airports and began the task of reforming the waterfront and coastal shipping. Competition was introduced into parts of the burgeoning telecommunications sector. Freight and grain handling were liberalised. government-owned business enterprises were also exposed to competition – though a planned partial float of the two government airlines Qantas and Australian Airlines was vetoed by the party’s National Conference in June 1988.

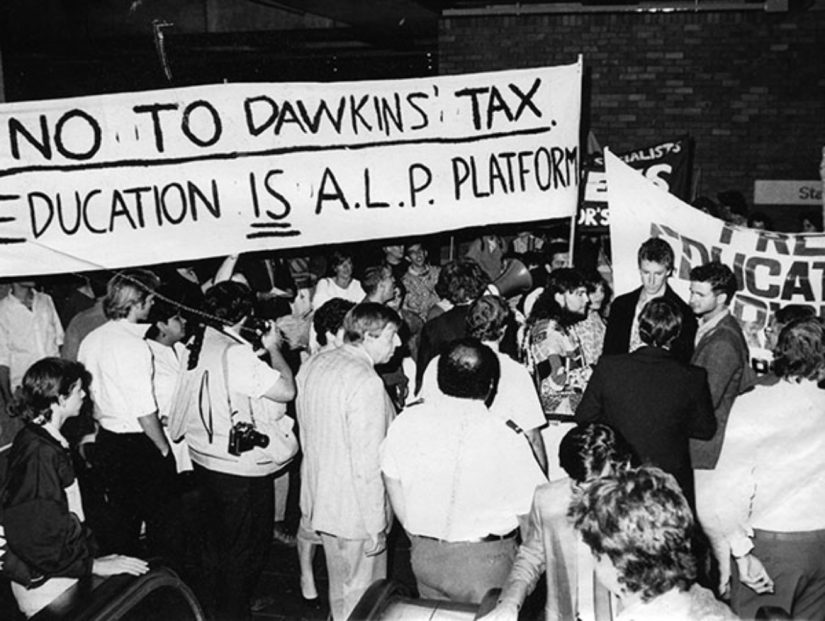

John Dawkins, now Minister overseeing a newly amalgamated ‘super-ministry’ of Employment Education and Training, restructured the institutions of higher education and introduced the innovative Higher Education Contribution Supplement (HECS), which provided students with income-contingent loans to be repaid after graduation. Through the Accord, complex craft-based industrial awards were restructured and simplified and some enterprise bargaining processes were put in place - the first steps towards dismantling the venerable institutions of centralised wage fixation.

Inevitably, however, these reforms cost jobs. Employers who had previously not had to worry about international competition now found themselves underinvested and overstaffed. Structural adjustment measures – such as training and education to help workers transition to new employment opportunities – did soften the blow. Aggregate employment grew strongly right through to late 1989. But many workers, especially male blue-collar workers in Labor’s industrial heartland, paid the price for a more competitive economy with their jobs. Labor would pay the electoral price, its primary vote shrinking.

The Accord, nonetheless, continued to make critical contributions to economic management. A further wage-tax deal saw unions agree to wage increases that were below the rate of inflation and linked to productivity improvements, in exchange for tax cuts and new social welfare spending worth more than $5 billion. Even with those outlays, Labor’s tight rein on government spending continued to reduce the budget deficit. By 1987, the deficit inherited from the Fraser Government had been eliminated and Treasurer Keating announced the first of three successive budget surpluses. By 1989, on a headline cash basis, the $7.1bn surplus was equivalent to 1.8% of GDP.

These reforms, significant in fiscal, economic and industrial terms, carried a powerful political message: the Hawke Government had rewritten expectations about how Labor should govern. Labor was improving social outcomes for many less-well off Australians – while also, thanks to more progressive taxation and targeted welfare programs, imposing fiscal disciplines and achieving budget surpluses. Labor was restructuring the machinery and institutions of capitalism – while also, through consensus and tripartite negotiations, reducing regulation and intervention, breaking down tariff walls and introducing more market-based competition into the domestic economy and internationally.

A Unique Partnership Backed and Deep Talent

Labor was superbly equipped, intellectually and politically, to undertake this peacetime reconstruction of the nation’s institutions and practices. Rarely had such a talented Cabinet or ministry been assembled across economic, social or international portfolios. Hawke’s chairmanship allowed for open debate, but outcomes were clear. Ministers shared a coherent view of the reform task they faced, were creative in developing policy in their portfolios, and were articulate and determined in prosecuting the reform argument in parliament, party, media and community. Rarely had the union movement been closer to the centre of government, its leaders exercising a broad and sophisticated influence over the direction of economic policy. Through collaboration and negotiated trade-offs - not strikes or other forms of costly disputes - working and low-income Australians won tax cuts, new safety nets, superannuation and free universal health and medical care.

Such outcomes exemplified Australian Labor’s distinctively labourist approach to government. No ‘Third Way’ philosophy, as Blair and Clinton would later define it, was deemed necessary; this was the Australian labour movement in partnership as it should be.

Keating told Parliament in 1988 that ‘in ten budgetary statements stretching back to 1983, we have painstakingly sifted through Commonwealth outlays, attacking waste, setting priorities and making quality changes with long-term beneficial effects.’ This effectively elaborated Hawke’s dictum of ‘restraint with equity’, underlining that when it came to the big policy questions, the Prime Minister and Treasurer were fighting side-by-side.

Leadership Tensions

The two Labor leaders were as different as a Perth-raised Rhodes scholar could be from a Bankstown boy who didn’t finish high school: Hawke the union advocate and consensus seeker, Keating the parliamentary warrior and caucus insider; Hawke the exuberantly-coiffed campaigner who exulted in a self-styled ‘love affair with the Australian people’, Keating the studious Italian-suited introvert and fancier of French clocks. At the podium, Hawke persuaded with the pugnacious insistence of an industrial advocate in the Arbitration Commission, while Keating slashed and battered with a witty, venomous intensity born in the backrooms of the NSW Labor Right. Yet they were highly complementary, and made a deadly combination.

Hawke and Keating secured the success of the Labor Government’s reforms by educating the Australian public, and not least the Labor Party, that these reforms were necessary to meet the national challenge of economic survival in a globalising world. Hawke recorded in his memoirs that he ‘spoke not only the language of change, but of interconnection between foreign policy and domestic policy.’ That was the key. In press conferences and media appearances, in parliament and party conferences, in local communities and international forums, Hawke and Keating were consistent and persistent - on topics ranging from immigration to trade to workplace training to the environment to gender equity - in arguing the urgent imperative of reform.

And yet, tensions were emerging between them.

In January 1988, Keating quizzed Hawke about how long he intended to stay as Prime Minister; he began to toy publicly with leaving politics to take up what he called ‘the Paris option’. Hawke, perhaps peeved by the glowing media reviews of Keating’s 1988 Budget, indicated that yes, the Treasurer would indeed be missed if he decided to go and live in Paris – but no, he was not irreplaceable. It was a minor spat. But it did not blow over. Keating colourfully fulminated about Hawke to NSW factional ally Graham Richardson; but their car phone conversation was eavesdropped and a transcript was leaked. Hawke called Keating and blasted him with language that he admitted later ‘would have emptied the bar at the John Curtin Hotel in my drinking days.’

The leadership rift now threatened to destabilise the government and jeopardise its election prospects; it required a patch. In November, Hawke and Keating agreed to meet at the Prime Minister’s official house in Sydney, Kirribilli House, along with two trusted friends, ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty and TNT boss Sir Peter Abeles. Before these witnesses, Hawke agreed that, sometime after the 1990 election, he would step down as leader and clear the path for Keating to become Prime Minister – if the agreement remained secret. Hawke had bought time, and Keating’s silence.

Meanwhile, Australians marked the bicentenary of British settlement. In January 1988, exuberant celebrations were held on Sydney Harbour. On the same day, indigenous Australians marched through Sydney in protest, challenging the celebration of colonisation and asserting the survival of their culture. The Queen visited Australia and opened the new Parliament House in Canberra on 9 May. Labor suggested that the first resolution in the new chamber should recognise Aboriginal rights to self-determination; Opposition intransigence stymied the idea. In June Hawke travelled to the indigenous community of Barunga (NT), where senior leaders presented him with a petition calling for negotiations leading to a treaty between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Hawke agreed that there should be a ‘proper and lasting reconciliation through a pact or treaty’ before 1990. Progress towards this ambitious deadline quickly stalled.

The Bicentennial mood was also harnessed by the Government in the quest for constitutional reform. Four referendum questions, based on recommendations of a Constitutional Commission, were put before voters: to extend parliamentary terms to four years, to provide for proportional representation (‘one vote, one value’), to recognise local government, and to enshrine certain rights and freedoms. All four were defeated, cynically exploited in an Opposition scare campaign. This followed the 1984 defeat of two referendums: to approve simultaneous elections of both houses of parliament, and to permit the interchange of powers between states and The Commonwealth.

Hawke moved to heal the scars of the 1983 leadership change by appointing former leader Bill Hayden as Australia’s 21st Governor-General. Hayden served with distinction at Yarralumla from 1989 to 1996. As Foreign Minister, Hayden and his successor Gareth Evans seized the opportunities created by the tectonic shifts underway in global affairs. The restructuring and new openness in the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, and the continued emergence of China created opportunities for multilateral collaboration and coalition-building by middle powers. Australia became an activist in international forums pursuing free trade, disarmament and environmental protection.

Leading on a world stage amidst rising economic challenges

Hawke successfully used the 1987 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) to push, over the objections of UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, for financial sanctions against South Africa - thereby isolating its white-led ‘apartheid regime’ from access to global investment and capital. In a triumphant visit to Australia in 1990, the newly-liberated Nelson Mandela acknowledged Australia’s role, and Hawke’s, in accelerating his release from prison, the end of apartheid and the emergence of a democratic multiracial South Africa.

Hawke also, with Keating, saw an opportunity to ban mining and drilling in Antarctica: through negotiating with the French government and renowned environmentalist Jacques Cousteau, Australia ultimately led Antarctic Treaty parties to agree to protect the entire southern continent as a ’Nature Reserve – Land of Science’. Foreign Minister Evans also led a patient and delicate regional diplomatic strategy that in 1993, under UN auspices and peace-keeping, culminated in Cambodia’s first free and fair elections; he was nominated for the Nobel Peace prize in 1992.

The high point of Australia’s multilateral diplomacy came in 1989, with Hawke’s initiative to create a new body to promote economic cooperation in the region and reduce trade barriers. Working first with South Korea and Thailand in January 1989, Hawke built regional support for the idea such that by November, he convened in Canberra the first ministerial meeting of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. The original twelve members – Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Japan, Korea and the six ASEAN economies – were later joined by China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and others. APEC was the embodiment of Hawke’s desired ‘enmeshment’ with the dynamic economies of the Asia Pacific – not just through increased trade and investment but also through mature political relationships.

The rationale for enmeshment was forthrightly set out by Ross Garnaut, Hawke’s senior economic adviser and then Ambassador to China (1985-88), in his 1989 report to the government, ‘Australia and the North-east Asian Ascendancy.’ The path forward was more difficult however. The death of Chinese moderate leader Hu Yaobang in April 1989 had sparked widespread popular demonstrations in Beijing and throughout China, leading to a ruthless crackdown by the hard-line Chinese leadership. On 4 June, 1989 troops massacred students and other protestors gathered in Tiananmen Square. Hawke, addressing a memorial service in Canberra a few days later, broke down in tears as he read out a diplomatic cable describing the killings in vivid – though, as later emerged, overstated - detail. Hawke quickly extended the visas of some 40,000 Chinese students in Australia.

As the Hawke Government prepared for the 1990 elections, it burnished its environmental credentials with the launch in July 1989 of a blueprint for a ‘Decade of Landcare.’ The far-reaching agenda announced by Hawke and Environment Minister Graham Richardson, with the support of both conservationists and farmers, included measures to reduce salinity, slow land clearing, protect habitat and plant one billion trees.

Labor’s credentials as economic managerswere, however, under serious challenge for the first time. The October 1987 crash in global stock markets had threatened to derail economic recovery. In the wake of the crash, the Reserve Bank delayed interest rate increases for fear of dashing confidence; but the boom resumed more quickly than expected, leading to a surge in imports that put further pressure on the current account. Rather than growing the productive traded goods sectors, investment chased unproductive assets – such as domestic property, which boomed. The economy continued to overheat and the RBA’s rate increases, when they came, came hard: official rates increased from 11% in May 1988 to 18.5% in December 1989. Several high-profile financial institutions and property developers, built on debt accumulated too easily in the deregulated financial environment created by Labor’s reforms, collapsed.

Adding to the political maelstrom, the (non-affiliated) union representing airline pilots went on strike in November 1989. Hawke and his government saw the pilots’ 30% wage claim as a direct challenge to the Accord, and refused to cooperate. The pilots resigned en masse and, amid chaos in the transport sector, were replaced by planes and aircrew leased from overseas supplemented – with Hawke’s approval – by the RAAF and RAN. The strike collapsed after 30 weeks but not without a bitter legacy. The Accord was saved but Hawke’s reputation for the reconciliation of conflict was damaged.

In these unfavourable political circumstances, and with unemployed pilots staging noisy protests wherever he appeared in public, Hawke called the election for 24 March 1990. The Reserve Bank was starting to cut interest rates, and the Accord delivered a sixth package of negotiated tax cuts and social wage increases, including expanded childcare and a doubling of superannuation contributions.

Liberal Member for Kooyong Andrew Peacock had returned as Opposition Leader - despite Keating’s barb that a ‘souffle cannot rise twice’ - and unlike in 1984 was clearly beaten in the leaders’ debate by a disciplined and succinct Hawke. Labor’s own leadership tensions having been stabilised at Kirribilli House, Hawke was able to exploit a divided and dysfunctional Opposition, delivering one killer blow: ‘a party that can’t govern itself cannot govern the country.’ Keating delivered another. When asked to respond to the Liberal attack line that ‘a vote for Hawke is a vote for Keating’, the Treasurer responded: ‘A vote for Andrew Peacock is a vote for Andrew Peacock. What you see is what you get: not much.’

At the ballot box, Labor’s primary vote fell again, to 39.4% – lower even than Whitlam’s second, disastrous, loss in 1977. Nine seats were lost in Victoria alone. But Labor had appealed for second preference votes from minor parties and independents, based largely on its superior track record on the environment. This proved decisive in getting over the line, with Labor winning marginal seats in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia. With a majority of eight seats, Labor was re-elected for its fourth term – an unprecedented achievement for the party at the federal level.