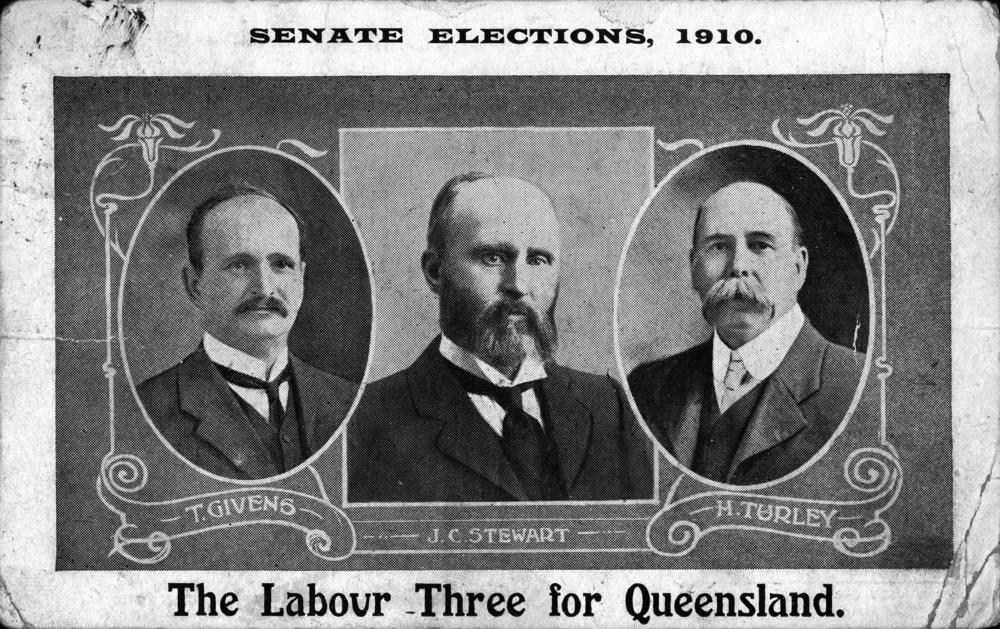

At the Federal election in April 1910 the fundamental issue was the reputation of both sides and a judgement about which was more likely to govern responsibly. Labor Party policy was presented as the unfinished business of the short-lived first Fisher administration, especially the resolve to gain control over the national economy by the foundation of a Commonwealth Bank, a new national currency, and gaining for the Commonwealth control over prices, incomes and industrial relations that the Australian Constitution had left with the States.

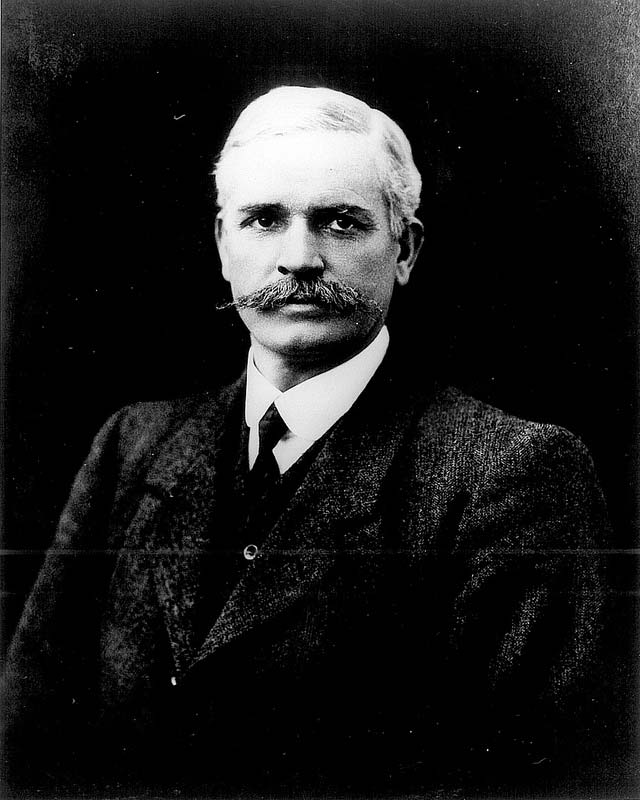

The new Fusion of the conservative parties probably worked to Labor's advantage in the short term as the electorate was being asked to vote for a new group that brought together two older parties who had been enemies for decades. Labor, on the other hand, had a united parliamentary team that had demonstrated its maturity and responsibility in two periods of minority administration. Andrew Fisher led the Labor Party to a convincing victory, winning 43 of the 75 seats in the House of Representatives.

This inaugurated the first majority Labor Government in the world. Indeed, it was the first majority Government of any party in the House. Labor had always regarded the terms of Federation as undemocratic in some of its details, and Fisher tried to address some of the problems. The Braddon Clause (s.87) of the Constitution provided for Commonwealth revenue until 1910. Fisher, as Treasurer as well as Prime Minister, guaranteed the continuance of revenue with the Surplus Revenue Act which continued Commonwealth control over tariffs in return providing a small return to the States. He supplemented this with a land tax which promised to break up large estates while providing further revenue to the Commonwealth. Fisher's vision was for the national government to take control over all economic matters, in line with Labor's arguments in the 1890s that a unitary system of government was preferable to a Federation. To his opponents in the conservative parties, and to some Labor Premiers, Fisher was a centraliser, trying to diminish States' rights.e Senate, the party won all 18 of the seats contested, giving it complete dominance in Parliament. Hopes were high among party supporters that the complete Platform would be legislated and that Australia would become the workers' paradise of their dreams. This was intensified when Labor won elections in South Australia in April 1910, New South Wales in October 1910, and Western Australia in October 1911. The promised land seemed to be in sight.

The Fisher Government delivered some important reforms, as did the new State Labor Governments. The Prime Minister had long considered the banking system as a servant of money power, and he was proud of his accomplishment in founding the Commonwealth Bank to restrain that tendency. An official Australian paper currency replaced the previous bills issued by individual banks. A graduated land tax was introduced that was designed to facilitate the breaking up of large estates as well as providing revenue. Improvements were made to the arbitration system and to the aged pensions scheme. Maternity allowances and a workers' compensation scheme for Commonwealth workers were introduced. National development was promoted, with a railway from Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta, while the Northern Territory was taken over from South Australia.

Labor had always regarded the terms of Federation as undemocratic in some of its details, and Fisher tried to address some of the problems. The Braddon Clause (s.87) of the Constitution provided for Commonwealth revenue until 1910. Fisher, as Treasurer as well as Prime Minister, guaranteed the continuance of revenue with the Surplus Revenue Act which continued Commonwealth control over tariffs in return providing a small return to the States. He supplemented this with a land tax which promised to break up large estates while providing further revenue to the Commonwealth. Fisher's vision was for the national government to take control over all economic matters, in line with Labor's arguments in the 1890s that a unitary system of government was preferable to a Federation. To his opponents in the conservative parties, and to some Labor Premiers, Fisher was a centraliser, trying to diminish States' rights.

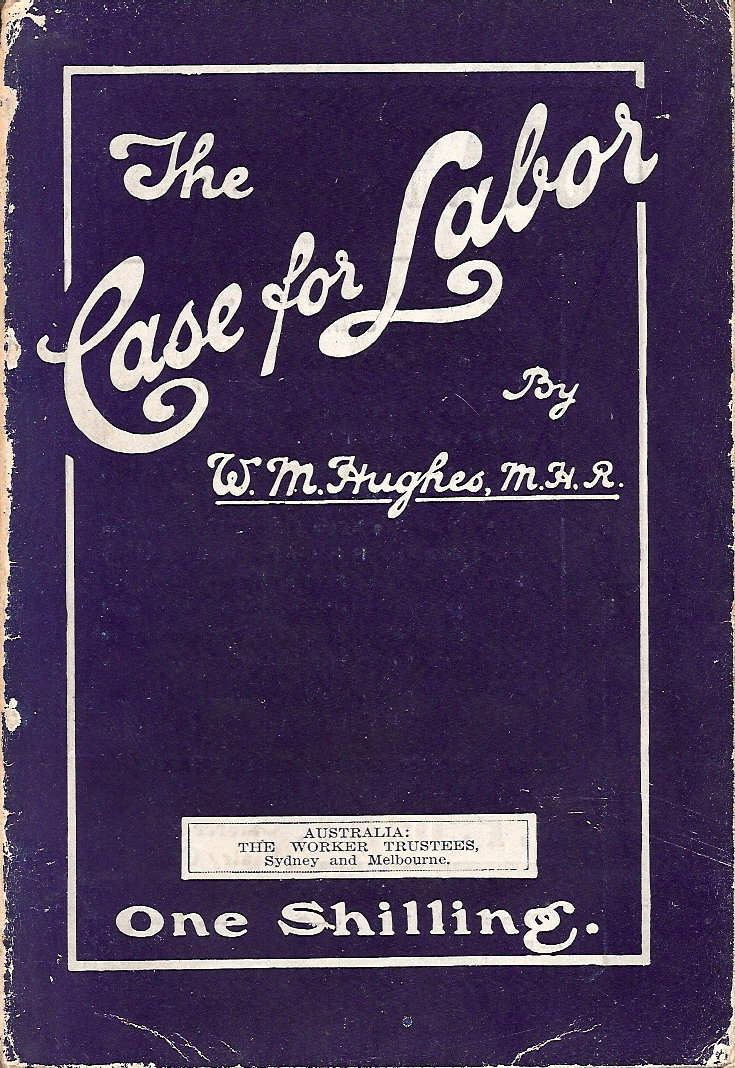

As promised, a referendum was held in 1911 to transfer power to the Commonwealth from the States over a number of economic matters, especially industrial relations. With Prime Minister Fisher away most of the year at the Imperial Conference (where the unprecedented presence of a Labor Prime Minister for one of the dominions was a source of inspiration for the still-emerging British Labour Party), this campaign was led by Attorney-General Billy Hughes. He engaged in a long drawn out conflict with the NSW Labor Government of William Holman, who disagreed with the policy. With Labor divided and the Liberals opposed, the referendum was easily defeated. A number of these provisions were re-submitted to a referendum along with the elections in 1913, but again were defeated easily. This was probably the biggest disappointment for the government, although even without this kind of control over the economy the achievements of the first majority Labor Government were easily the most comprehensive and progressive of any government in the short history of the new nation.

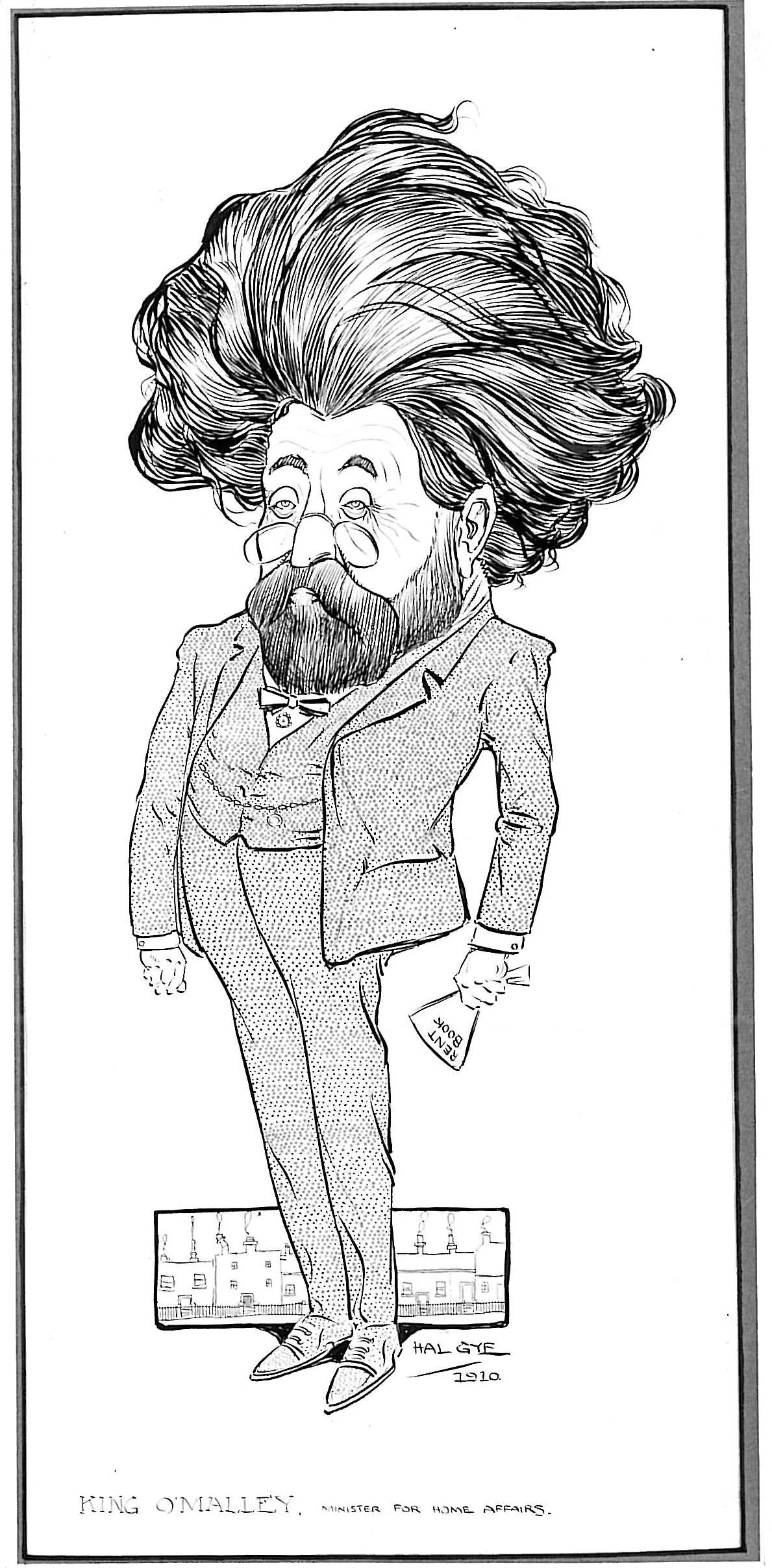

One of the key figures in the Fisher Government was the Minister for Home Affairs, King O'Malley, member for the Tasmanian electorate of Darwin. With uncertain origins in North America, O'Malley was one of the most colourful personalities in the party a teetotaller, a ladies' man, flamboyant in his use of slang and in his outrageous clothes sense. He shared with Fisher a distrust of money power and claimed for himself the credit for founding the Commonwealth Bank (although Fisher himself was more significant in that decision). In office O'Malley moved quickly to confirm Canberra as the site of the national capital, awarding the prize for planning the city to Walter Burley Griffin, and in February 1913 at a formal naming ceremony driving the first peg on the open spaces of the future city. He is also credited with confirming as official the customary spelling of the party's name as 'Labor', not 'Labour' in 1912.