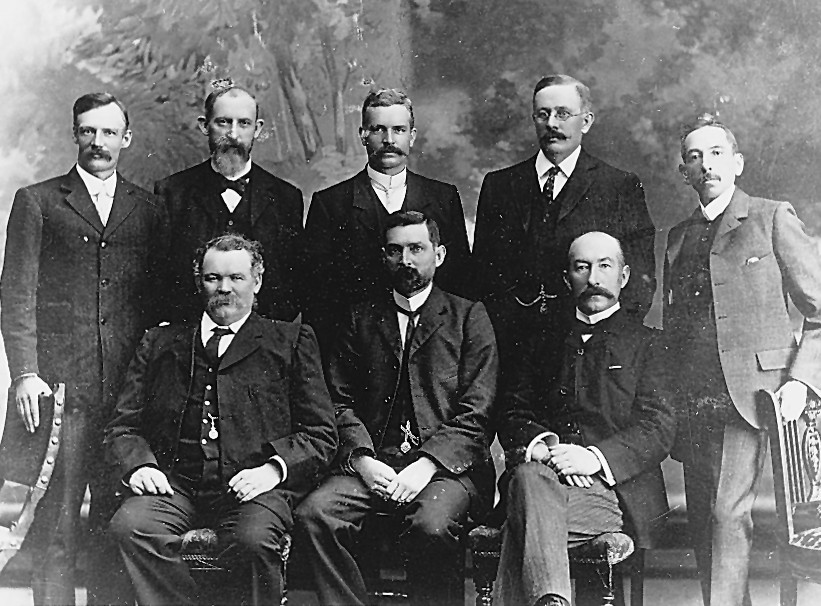

The answer was revealed within months. In the debate on the Government's Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, Deakin refused to accept a Labor amendment, and treated the ensuing vote (which was defeated by the combined votes of Free Trade and Labor) as a vote of confidence. He resigned his commission and advised the Governor-General to appoint Chris Watson as Prime Minister. Caucus would not contemplate forming a coalition with Deakin. The first Federal Labor administration took office on 27 April 1904, with a very impressive line-up of Ministers: Chris Watson, Billy Hughes, Egerton Batchelor, Andrew Fisher, Senator Anderson Dawson, Hugh Mahon and Senator Gregor McGregor. Also included was Henry Bourne Higgins, not a member of the party, but a sympathetic Protectionist. All had been chosen by Watson who was given a free hand by Caucus.

The new Labor Government was opposed in the House by two fiscal parties whose combined vote could bring down the Government at any time. Yet during its tenure of just less than four months it accomplished a great deal. There was little opportunity for new legislation, although the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, passed at the end of that year, was pushed towards resolution. Although Alfred Deakin was personally sympathetic to much of Labor's agenda, he was very suspicious of the Labor party's extra-parliamentary organisation and any talk of 'socialism'. Moreover, many in his party were quite hostile to Labor. When Watson approached him to get some guarantee of continued support in office Deakin refused, and a minor disagreement over the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill was enough to see the votes of Free Traders and conservative Protectionists bring down the government.

The most important achievement of the first Labor government was not in any policy initiative, but in the image of responsibility, pragmatism, and responsiveness to the electorate portrayed by the new administration. The three and a half months proved that Labor could be trusted in office, and thus demolished one of the strongest emotional arguments of its critics. Labor would continue to be portrayed by its enemies as a bunch of revolutionary 'socialists', but only a minority of the electorate would believe it. From that time confidence increased in the party that it could win majority support.