The early Labor Party had to identify its social base if it wanted to have continuing and improving electoral success. Obviously it made an appeal to trade unionists. However, most workers were not unionists at this time. Even many trade union members in the various colonies had developed an allegiance to protectionist parties that promised to protect jobs and industry. From the beginning until well into the next century, the main social base of the party was in rural districts where the AWU, mining and railway unions were strong and where workers in country towns identified the conservative parties with big city interests.

The initial success of the Labor Party drew many other organisations and movements to seek some kind of common cause. Female suffragists, for example, saw the party as more likely than the conservative parties to promote women's political rights, although male trade unionists could be just as chauvinistic as male employers. At least in this period, the Labor Party was in advance of the conservative parties in promoting policies to protect children and to give support to families. The temperance movement, which was very important at that time, also tried to exert an influence on the party, arguing that the interests of workers would be best advanced by getting them to abandon alcohol. Most leaders of the party in all the colonies in the 1890s would have agreed that grog was a major social problem for workers and that some control was necessary. Many were teetotalers. Meanwhile, and with more eventual success, the liquor trade saw an opportunity to maintain its place in society by identifying itself with Labor, as temperance bodies succeeded in having a greater influence on conservative parties. Any mass political party has to promote itself by attracting the support of pressure groups in society. This was the beginning of a long history of such political alliances.

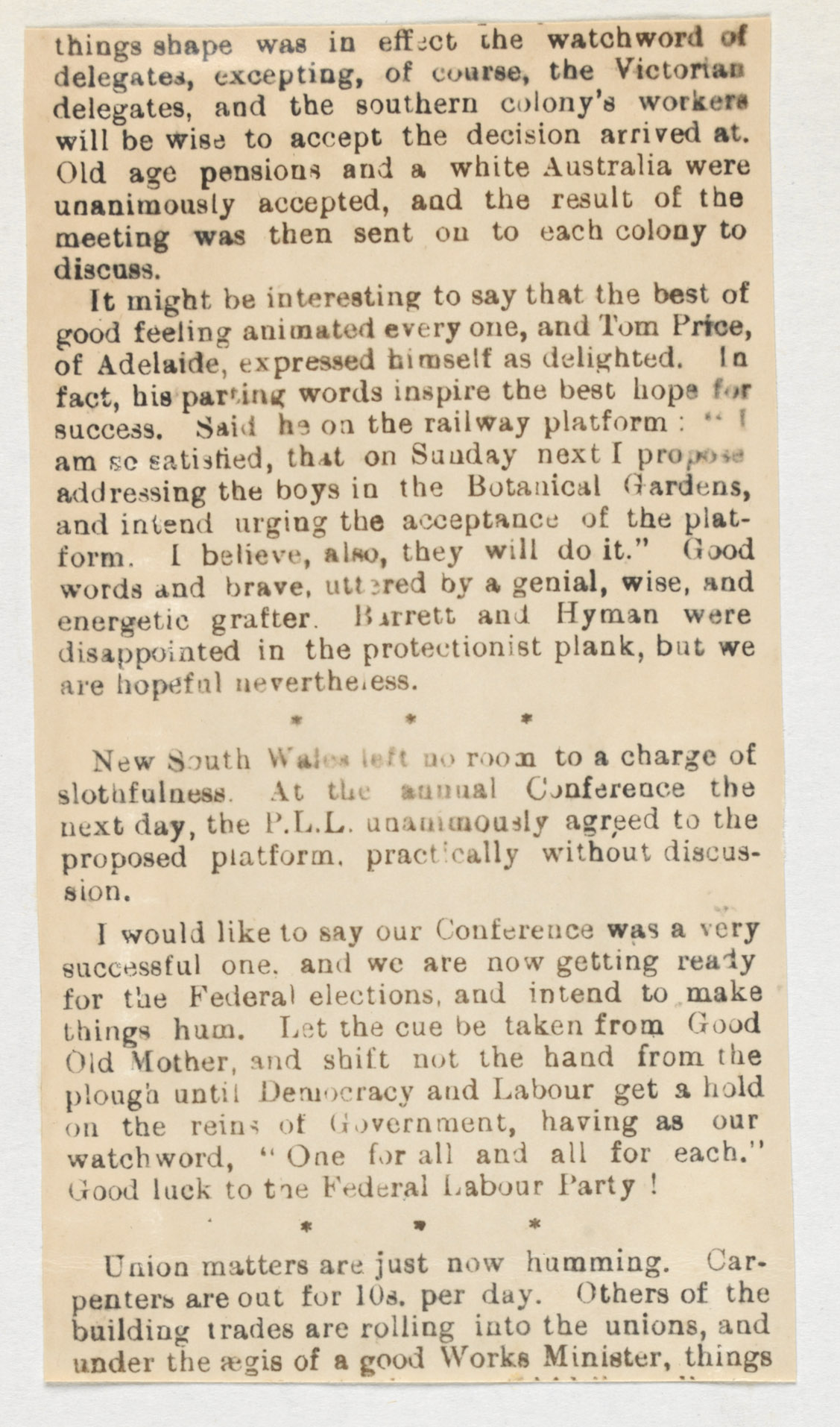

When it became clear that a newly federated Australia would become an important, if not the most important, focus of politics, there was little disagreement that there should be some kind of coordination between the existing colonial Labor Parties. In most colonies, which were about to become States of the Commonwealth, serving MPs were the only people capable of effective national coordination, since the extra-parliamentary organisations were still very weak. The inaugural Federal Conference (it was called the Intercolonial Conference for most of the first decade of the new century) was largely the initiative of the New South Wales PLL and brought together delegates from four of the colonies, with only Tasmania and Western Australia absent, although they quickly joined so that the new national party could contest the first Federal Elections in 1901. The Australian Labor Party began as, and remains, a federal party, with power devolved from State branches to the centre, although the evolution of power relationships has meant that more control has gravitated to the centre over time. There was considerable debate over a proposed Federal Platform. Otherwise, the only real task for the new national party was to organise for the coming Federal election, and that was resolved by leaving the electoral machinery almost entirely in the hands of the State bodies. No Federal Executive was constituted, and no permanent national machinery was recommended at the first conference.